Medical Illustrator

Career Profile

Please introduce yourself (what is your current training/educational status and/or where do you work?) and share with us how you decided to get into scientific visualization.

Hi, my name is Paul Kelly. I’m a 2011 graduate of the Biomedical Communications masters program at the University of Toronto–Mississauga, and a Certified Medical Illustrator. I currently work at the Toronto Video Atlas of Surgery (TVASurg), where I’ve been since 2012. While I have enjoyed making art ever since I was young, my love for making images took on a new purpose during my undergraduate studies in kinesiology at UIC (University of Illinois) in Chicago. I was constantly sketching in my notebooks to understand material better, and when I saw a presentation from a medical illustrator during one of my courses, I was hooked.

What do you like the most about this field?

I often joke with my family about how I essentially live the life of a retired person: everyday I have fun learning about things that interest me. I love that this field involves constant discovery and problem-solving. I love that I get to interact daily with passionate, talented, and highly intelligent people who help me to progress in my own pursuits. I love that I get to learn about niche areas of science, medicine and human anatomy, and share those findings with the world in ways that will make a positive impact on other people’s lives. I love that my job, as the botanical artist Keith West describes, neither pollutes nor guzzles the Earth’s resources.

How and where did you acquire your current skillset in scientific visualization? Was it all via a graduate or other program or are you self taught? If so, did you use any particular online resources to help with your training?

My skills were definitely honed and accelerated during my graduate studies, but they didn’t begin or end there. Before grad school I became obsessed with life drawing, and continue that line of study to this day. There’s always more to learn when it comes to drawing the human form, and I firmly believe this is the best foundation for our craft because the visual problem solving involved translates to everything you have to do as a medical or scientific illustrator.

There are lots of great resources for online learning, many of which were not available when I was beginning my voyage into the field, but now as a professional, I love being able to make use of. For people looking for some great resources to level up their visualization skills, I’d recommend checking out Drawabox.com for basic drawing fundamentals, Vitruvian Studio for illustrative realism, and LearnSquared for CG production. There are many other great resources out there, these are just the ones I use actively.

What do you consider some of the biggest barriers to entering the field? Are they technical, training, scientific, professional (availability of jobs or projects)?

I think the biggest barriers are both psychological and logistical.

The first is recognizing that if you aspire to be a medical illustrator or scientific visualizer, you need to have a strong grasp on not one, or two, but three different modes of thought (sometimes more). If your background is art, be prepared to navigate some hard science. If you’re a scientist by training, expect to spend some serious time picking up a new skill set that may feel foreign to you. For everyone, and this is mostly overlooked in the beginning but becomes obvious later on, the value of business know-how can not be ignored or bypassed. In order to continue working as a professional in the field, you will inevitably come to a point where you need some serious business skills, including but not limited to: marketing, negotiation, and finance tracking. Business isn’t just boring paperwork though–the business aspect is how you manage human interactions as it relates to your craft. When you find your ideal clients and forge relationships with people who want to see you succeed, business becomes exciting.

If I may be candid, I think money is one of the biggest barriers into, and within, our field. Not necessarily the money one has available per se, but definitely how we think about it. We must always remember that money exists as an exchange of value, so, you should get what you pay for, and you should deliver what you’re paid for. Tuition for grad school is the #1 issue I find young people hoping to enter the profession running up against, and I think they want to know if it’s going to be worth it–will paying for school or training help them get a job? I can only speak from my own experience, but I would tell those people my grad school education absolutely prepared me for my job. My job would never have existed if I didn’t go through BMC.

I don’t think financial concerns should be the one thing holding anyone back from their dream. I think if you are committed 100%, and can demonstrate your passion and work ethic via a portfolio of finished works, then opportunities will be made available to you. Yes, tuition is expensive, but there are scholarships available and not every program charges the same. Tuition may be different depending on where you live. There are undergraduate programs as well which are quite good and may be more affordable.

Barriers to entry will be different depending on the individual, but for just about everyone I think it’s helpful to hear that whatever barrier is yours, the method you devise to clear that hurdle will itself become a powerful tool that will serve you well in all your future pursuits, within or outside of professional work.

Which practitioners (or what visualizations) have been most inspirational to you?

There are so many artists in our field that have blown me away with their beautiful work, it’s hard to name just a few, but one person who has always stood out to me as a high standard of craftsmanship is Dr. Sarah Simblet from Oxford. That’s a PhD in drawing by the way. She’s published books on anatomy but her specialty is botany illustration, and she’s phenomenal. Every time I look at her drawings I am awed at the level of understanding she has of her subjects, and elegant, pragmatic design. You have to see her illustrations in the book “The New Sylva” to really appreciate her drawing skills.

Now, going back to my earliest memories of something that inspired me (and continue to inspire me), is a Disney short that I think everyone in our field should watch: Donald Duck in Mathmagic Land. The use of visual analogies to teach difficult concepts is something I’ve always aspired to emulate in my own work.

Which conferences would you recommend to those interested in this field and why? What particular insights or benefits did you get out of attending this (these) conferences?

The Association of Medical Illustrators (AMI) annual conference is the place to be. Here you will find the leaders in the field presenting their work and discussing the topics they care about. Attendees have the opportunity to see in person working professionals from a multitude of sub-specialties, hear about new developments in science and technology, and learn visualization techniques and business strategies they can put into practice immediately.

If there was one resource, tool or conference that you could wish for to facilitate your work, what would it be?

I would love to check out SIGGRAPH. Unfortunately I didn’t get the opportunity to go in the past and I hope to get another chance in the future. I may try to attend virtually this upcoming year if that’s available. I’ve always been impressed by that conference and it seems like the place to go to find out about the cutting edge of technology used in the visualization industries.

What other advice would you offer those interested in either a professional or full-time academic career in scientific visualization?

Having made many mistakes and endured numerous failures, I would encourage folks entering this industry to keep a few things in mind: Always have a passion project on the side. Too much overtime can destroy your eyes, wrist, posture, and sanity, so take appropriate breaks. At the same time, keep pushing your skills and stay on top of new software, don’t coast. You can’t and won’t escape the business aspects–learn to love writing well-written contracts, agreements, project charters and SOPs. Take extreme ownership of everything. Most importantly, it’s not about what you want to make, it’s about what other people need to communicate and how you can help them do that.

Please comment briefly on the samples/links that you have submitted for this profile… why in particular are you proud of these and what do you hope viewers will notice and get from seeing them?

The pieces I’ve included are ones that hold a significance to me for various reasons, or I distinctly remember I enjoyed making them.

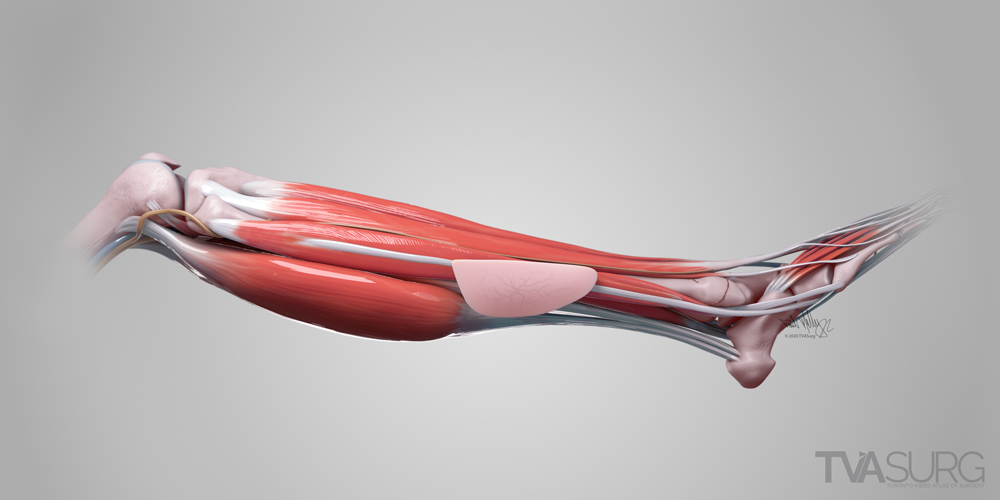

One of my recent solo cases at TVASurg was for ENT surgery, an osteocutaneous fibula flap harvest technique. This was a challenging case because I had a tight deadline, but I delivered the final animation on time. I continued to play with the assets after launch, which included re-rendering them in Arnold so that I could better familiarize myself with that workflow. I tried to pay careful attention to the direction of muscle fibers when sculpting the muscles of the lower leg, because in a lot of these ENT flap harvest cases the muscle fiber direction serves as a landmark and confirms which muscle they are looking at. I also went in with Photoshop and painted an indication of the vascular bed of the cutaneous perforator under the skin, because that’s what they are aiming to harvest from the skin island portion of the flap.

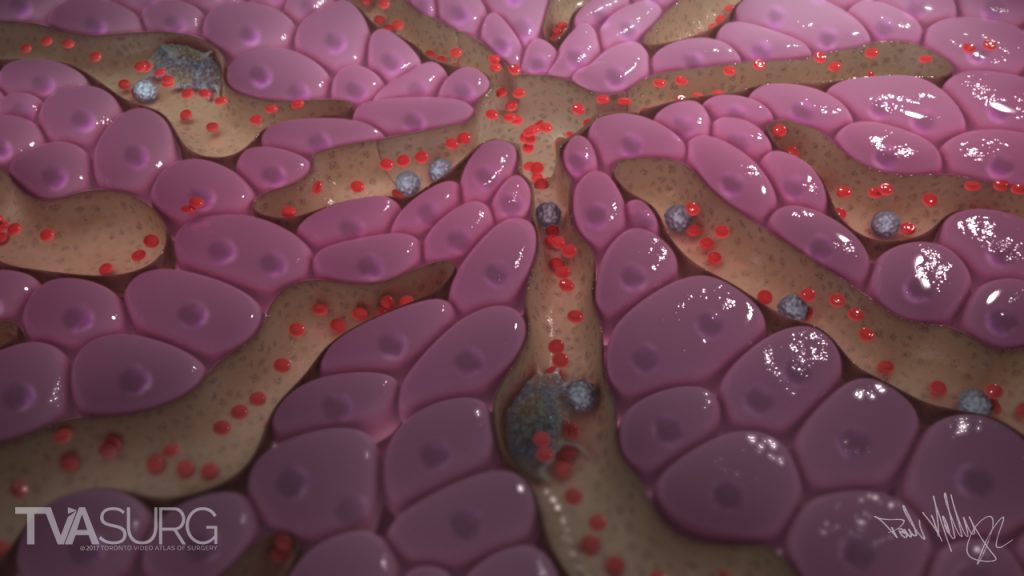

The cellular landscape of hepatocytes and sinusoids was a shot from an animation short we made at TVASurg in the summer of 2017. This was a passion project the team took on in lieu of an annual demo reel. We wanted to push our skills and try out some new subjects we don’t get to venture into all that much in our regular work. It was a fantastic learning experience and a prime example of what I mean when I talk about passion projects. I came up with the idea while watching the TV series “Westworld”–I was blown away by the opening credits to that show and wanted to attempt a homage to it, using similar themes and rendering style, while breaking off in a different narrative direction. One of the themes in that show is the callous way in which androids are routinely killed and repaired, and the way the humans in that fictional world take organ regeneration and tissue repair for granted. I wanted to address the parallels I see of this mindset in our own world, and draw attention to the fact that it’s only because of the generosity of organ and tissue donors that we can treat and save patients with certain conditions. These folks can’t wait for medicine to catch up with science fiction, they need a new organ yesterday.

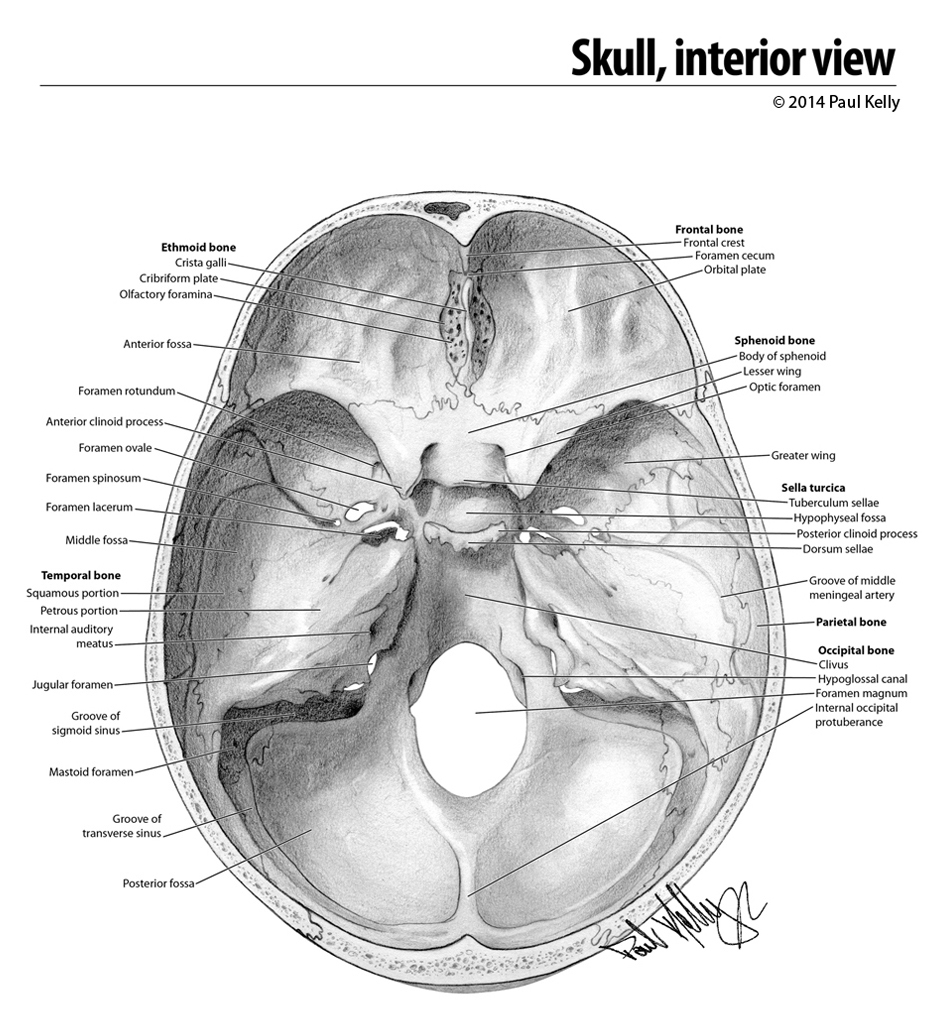

I also wanted to include an example of one of my CMI (Certified Medical Illustrator) certification pieces. I took on the CMI qualification as a personal challenge to push myself and I’m glad I did. I encourage everyone in the field to pursue this certification because I think preparing for the written and portfolio exams are an excellent way to sharpen your game. This drawing fulfilled one of the portfolio requirements. It took multiple attempts but I’m happy with the end result. I think it’s important to keep in touch with the roots of my discipline even though most of my professional work involves video. I still love to draw and definitely consider it to be the foundation of medical illustration work.

Where do you think the field of scientific visualization is ‘going’? Do you perceive any trends in its evolution or are there certain directions that you would like to see implemented?

I think VR is going to continue to gain traction, and we’ll see a convergence of gaming and 3D animation workflows to better tell stories in virtual environments. Multiplayer VR simulations will definitely be a thing (they already are). I think we’ll see a lot of multi-disciplinary teams emerging and the ones who can combine different specialties and personality types the most seamlessly will be successful.

I’ve been really interested in photogrammetry over the past few years, not necessarily because I think it will take over 3D modelling (I don’t think it will), but because it represents a new connection between what we interact with in the physical and digital spaces. It’s a method of bridging the two in a direct way. I think this and similar tech like AR/MR will become more common.

And then let’s end with a simple question… What is your ‘10 year plan’ in terms of what you hope to accomplish in scientific visualization?

I have recently launched a new website with a few of my favorite pieces from recent years, but it’s nowhere near done. I’ve only posted roughly 20% of the work I’ve accumulated from working professionally, and I want to get that out there so people can see what I’ve been working on and hear it described from my point of view as the creator.

One of the features on my site I was most excited about was having a home to post my new podcast on the field of medical illustration. I have wanted to do this for a while now, and I am happy to have this work underway. Over time my goal is to carry on conversations with all of the people in this industry who have inspired me, and whose work I feel is pushing the boundaries of scientific understanding and raising the bar of aesthetic quality. I also want to have discussions with other artists and scientists who aren’t directly involved in medical illustration, but who I see as folks who do work I think will resonate with everyone in our field.